Git rebase, rolling back commits, and a Sourcetree caveat

- A typical rebase flow

- Rolling back local commits

- The main problem with

rebase - Sourcetree caveat

- References

Until recently, I used mostly merge operations in git. However, recently I have been using rebase more often.

I always regarded merge as generally safer option, although it made the commit history more noisy due to the merge commits that are introduced whenever we merge a branch into another. This noise can add up when many developers are collaborating across multiple branches of the same repository.

-

When you

merge, you keep information about the commit from which you branched out of, and the merge commit marks the merge back into the base branch after your work is done. You know when you pulled new changes from the base branch, and when it was merged into the main branch. This keeps the full branching dependencies and history, but can make the git flow very noisy in large teams! -

When you

rebase, the commit timeline of your branch will stay linear even when you pull new changes from the base branch — but the timeline will give you no idea of when you actually pulled those changes. The dependencies between branches will also be lost, since you are copying commits from one branch to another instead of adding new merge commits. This keeps the history cleaner at the cost of traceability.

A typical rebase flow

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

# featurebranch contains your new commits (feature branch) that you want to rebase.

# most likely you will already be in your feature branch, so this command won't be

# necessary.

git checkout <featurebranch>

# originalbranch is the branch from which you branched out to develop your feature.

# By rebasing from that branch you will retrieve all newer commits and clone them

# into new commits in front of the last commit in originalbranch.

# These will be new commits, with new hashes, but with the same changes.

git rebase <originalbranch>

# If any conflicts emerge, you will

# have to solve the conflicts...

# After solving the conflicts, add changes to the index:

git add .

# continue rebase to next commits, or until conflicts are found...

git rebase --continue

# ****Keep fixing conflicts, adding changes and continuing the rebase****

#

# This will continue until no more conflicts have to be solved and all commits

# from the <originalbranch> are rebased into <featurebranch>...

#

# When rebasing is finished, let's push our changes.

# Avoid git push --force at all costs, since it will rewrite the remote history.

#

# If other people pushed to the same branch in the meantime, all those commits

# WILL BE LOST!

#

#

# Instead, use git push --force-with-lease, which will refuse to perform the push

# if newer commits are found in the remote branch (i.e. local refs differ from

# remote ones).

#

# Do not perform git fetch before this, as it will effectively equal a

# git push --force, which forces the remote history to be rewritten,

# potentially wreaking havoc if others pushed to the remote branch

# meanwhile!

git push --force-with-lease

Rolling back local commits

Rolling back commits can be a good way to clean up your commit history, i.e. squashing many commits into a single one. To roll back commits while keeping the changes made to those files, you can use:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

# in this example, we will roll back the working copy by two commits

# but changes will be kept in the local files

git reset --soft HEAD~2

# when you run git status, all changes made by the two rolled-back commits

# will be shown:

git status

# add changes to the index for a new commit

git add .

# add new commit with all the changes from the 2 rolled back commits

git commit -m "adds feature XPTO"

# push history (will overwrite local branch if no other commits where pushed meanwhile)

git push --force-with-lease

# confirm changes. A single commit will be added to the timeline:

git log.

The main problem with rebase

Because it rewrites history in your local branch, rebase should never be used on branches where other people are working, or in other words, public branches.

Quoting Atlassian’s on Merging vs. Rebasing:

The rebase moves all of the commits in `main` onto the tip of `feature`. The problem is that this only happened in your repository. All of the other developers are still working with the original main. Since rebasing results in brand new commits, Git will think that your main branch’s history has diverged from everybody else’s. So, before you run `git rebase`, always ask yourself, “Is anyone else looking at this branch?” If the answer is yes, take your hands off the keyboard and start thinking about a non-destructive way to make your changes (e.g., the git revert command). Otherwise, you’re safe to re-write history as much as you like. (...) Again, it’s important that nobody is working off of the commits from the original version of the feature branch.

Sourcetree caveat

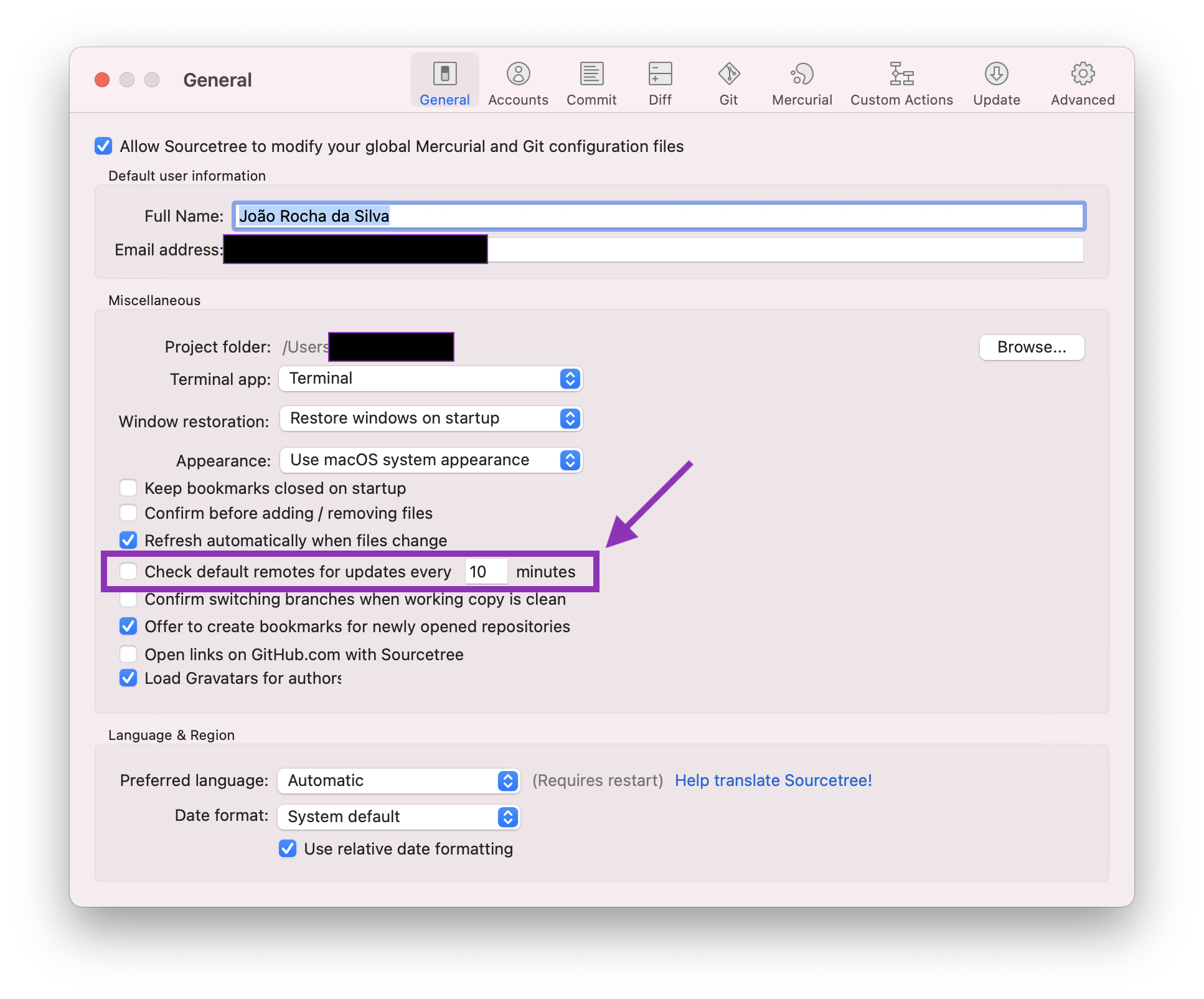

Source tree will automatically run git fetch commands when it is open, updating the local refs to match the remote ones. This is a problem, since a git fetch followed by a git push --force-with-lease is the same as a git push --force ! To avoid this, deactivate the auto-fetching behaviour of Sourcetree:

References

Merging vs. Rebasing, by Atlassian.

Comments

Post comment